Tell us about yourself – who are you? What do you do?

My name is Chris Renshall. I am a securities analyst by day, board game social media freak by day, publisher/designer by night and weekends. I read a lot of financial reports and news and look at spreadsheets for my day job.Because of this I have to work really hard to not make all my designs financial game.

I am lucky enough to have a job that allows me to be on social media all day while I get my day job work done at the same time. Because of that I get to spend a lot of time getting to know and chat with the great game people on twitter and I have recently jumped into the learning curve that is BGG.

This post has affiliate links, which directly support Andhegames.com at no extra cost to you. If you have any questions about anything recommended, let me know. – Andrew

What board games are you playing most right now?

Total designer answer coming up….prototypes. I do have a weekly group that I attend on a semi regular basis. We play a lot of Resistance and Avalon to start the evening when the large group is there. We then break up and I am trying to play as many different games as possible since the number of different games I have played is quite low.

Two games I love right now for Evolution and For Sale.

One fact that we probably don’t know about you:

I am a designer that got into gaming rather than a gamer that wanted to try their hand at design. Aidan, my co-designer, and I bought a football game (American) a couple years ago and it was terrible. We started talking about how we would improve it and then we started to write those ideas down and then we made a prototype and then we played it and it was fun. Then we thought about designing other games at which point we realized that we no idea what games were out there other than Catan. I then jumped into research and playing games. While I don’t get to play games near as much as I would like, there is a lot out there for me to play and learn.

What are you naturally good at that helps you in your work?

Project Management, Idea Generation and a natural desire to break the games I play. making games is a massive project undertaking and having the skills to organize the to do list of making a game makes the process so much easier. I don’t know where it comes from but I can get game ideas from all kinds of places. I wish i had known about game designer earlier in life. Then I could have applied all these idea generation skills earlier and been producing games already, haha. Wanting to break games really cuts down on play testing time when the game is in front of other people because we have already broken the game multiple times before we let people play it.

What are you not naturally good at, that you’ve learned to do well anyway?

Social Media, at least I think I know it well enough to function with competence.

Describe your process (or lack thereof) when making games. How do you reach your final product?

I think I will direct you to this blog post of ours. This is basically our process.

What design-related media do you consume on a regular basis?

Cardboard Edison, Building the Game (vidcast and podcast), Jamie Stegmaier Blog, Ludology Podcast, Talking Tinkerbots Podcast, Meeple Syrup, Funding the Dream Podcast….I know I am leaving some out…

(That’s plenty. Thanks! –A)

What are some tool/programs/supplies that you wouldn’t work without?

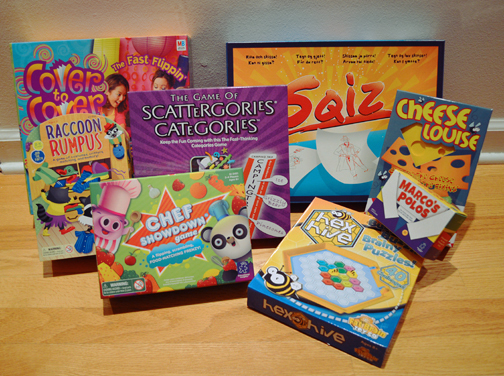

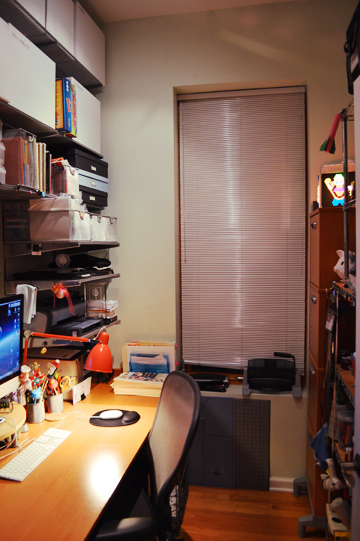

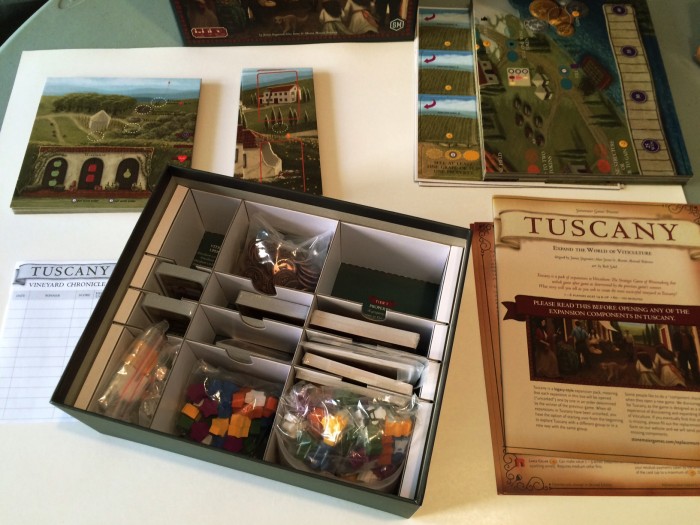

Notebook of some kind always at the ready. My designer box of many things. Google Docs. Dropbox. Access to Twitter and YouTube, really.

(I’m surprised that he’s the first designer to mention Dropbox. Dropbox is the best! –A)

What’s your playtesting philosophy? How often/early do you playtest?

Test as early as you can and learn how to ruin your game from the start. Test your game as you are forming the idea. Use a lot of thought experiments. I do a lot of pacing when I design games. I play out a mechanic over and over using min/max strategies to think about what would happen with the mechanic. Aidan and I playtest a lot, we don’t get to test as often as we would like in the late stages of testing.

What are some of the biggest obstacles you’ve faced in your work, and how have you overcome them?

Learning the logistics of this industry and trying to cut down on the time sink that is making a game. We could probably fully develop a game or two per month(physical production not included) if we have a network of reliable playtesters and we were able to do this for a living. That may sound lofty (it might not, I don’t know) but we work fast and while it may not be sustainable long term, we have a backlog of ideas that if we could focus on making games full time, we are excited at the possibilities of what we could produce as far as the number and quality of games of concerned.

Getting the people together is difficult because people have lives and we are not in a position to pay people to play our games. But this is all part of the process of becoming a company. The other big obstacle is the amount of stuff we need to learn. We still need to learn a lot about the business side of things. There is a lot to wrap our heads around and that is what I will be spending the next month or two researching.

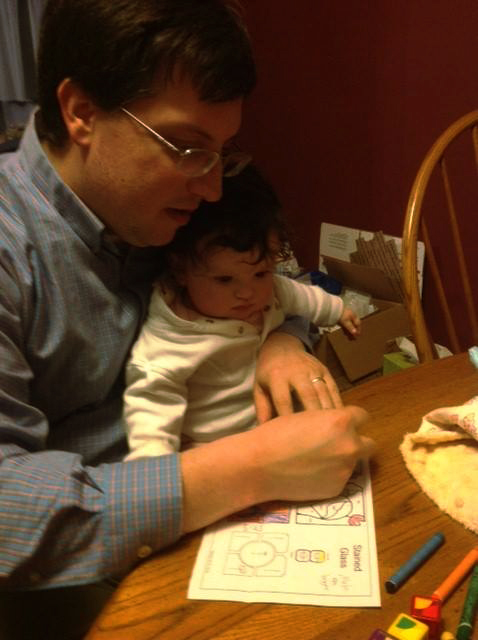

How do you handle family/work balance?

I am lucky that my wife works later than I do, so I have 2-3 hour windows from when I get home to when she gets home where I can get a lot done in the design/blog/research departments. She is also a late sleeper on the weekends so that means Aidan and I can get together in Saturday mornings to work on what we need to work on. Not to say I have not hit bumps in the road, I am still figuring out all that is required to make the game schedule work with regular life things. It really helps that we don’t have any children (yet) but for now I am able to dedicate a lot of time to this. Hopefully I can make this my full time job before my time availability goes away.

Do you have a second job? If so, what do you do? If not, when/how did you quit your day job?

I work as a securities analyst for a hedge fund. I read a lot of financial reports and work with spreadsheets most of the day. I also read a lot of financial news.

How many hours/week do you generally devote to game design? How many to other business-related activities?

Not enough….20-30 hours per week total. Of that, I probably so 2-3 for game design. The rest is spent on research, writing, getting our name out there. Just a lot of time needs to be spent on getting to know the people, the games and all that is the board game world and making sure they get to know who we are as well.

What’s the best advice about life that you’ve ever received?

I am not a movie guy, but movies have some great lines in them. Andy Dufrain said “Get busy living or get busy dying.” The movie, About Time, is a great lesson about what we do with the time we have. I don’t think I could pinpoint a moment that would qualify as the best. Just the realization that life, to me, is too short to spend watching loads of TV and doing things that have no tangible outcome.

What one piece of advice would you give aspiring game designers?

If you want to makes games for your friends and family, make you games however you see fit using whatever resources you can find and have fun with it. If you want to have any level of commercial success, designing the games is the furniture of a house you need to build. You need to build a foundation, strong walls, extra rooms for potential growth, quality plumbing and electrical systems that will last a long time. Designing games is the fun stuff at the end after the walls are plumb and leveled and all the bits in the wall are inspected and made from good parts. If you are not prepared to do A LOT of behind the scenes legwork, you will hit “the wall” (see what I did there!). I would not want a new designer to give up because they did not know the amount of work that goes into making this dream a reality.

Who would you like to see answer these questions?

The Talking Tinkerbots Crew and My co-designer Aidan, but I know most if his answers to these questions!