Tell us about yourself – Who are you? What do you do?

Hi! My name is Emily Care Boss of Black & Green Games. I am a game designer and independent publisher of analog role playing games. I live in western Massachusetts in the US, and work at a land trust conserving land for my daily bread. Back in the 90s when I was in college was when I got into role playing games, and I started designing in the early 2000s as part of the Forge forums community. Print on Demand technology had just started to make it feasible to print books in small print runs. You could now print books in the dozens or hundreds, rather than in the thousands which had been necessary before. And with pdf distributing and online store fronts using Paypal and other virtual payment options, it meant us small folks could make a game and not break the bank. Crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter and Patreon have reinvented the independent publishing game all over again now, making it even more accessible. This is an amazing time to be gamer!

Since then, I’ve published eleven of my own games, including my Romance Trilogy: Breaking the Ice, Shooting the Moon and Under my Skin; collaborated on five more including Play With Intent with Matthijs Holter and Alex Fradera, and Dread House, and a haunted house adaptation of Dread (which was recently featured on Wil Wheaton’s Tabletop) for kids and adults, with my husband Epidiah Ravachol. Eppy & I met at JiffyCon, the local game convention I started here in Massachusetts. I also got to work with a ton of wonderful fellow women game designers, writers and artists by editing the RPG = Role Playing Girl Zine in 2009 and 2010.

Some of my games are live action role playing games. I wrote What To Do About Tam Lyn? with my friend Julia Ellingboe, about fairies and mortals coming to the Fae Queen’s court to decide the fate of lovers like Tam Lyn and his beloved Janet. The third game in my Romance Trilogy is a freeform larp, Under my Skin, about a circle of friends how all start falling in love with the wrong people. Under my Skin was influenced by a group of Nordic game designers called the Jeepform Collective, who write games about real world stories of love, loss (and occassional hilarity). After I played a few Jeepform games, I fell in love with this style of play and have written more, like Remodel about four women helping each other remodel a house and cope with major changes in their lives, and Play With Intent, which is a customizable play set which steals borrows liberally from Jeepform, improv acting, tabletop rpgs and more. There are a lot of people in the US, Canada and elsewhere writing this kind of game some of which have been collected under the style label American Freeform, others of which were submitted to a design contest called The Golden Cobra Challenge.

These days I write at my blog Last Chance Noir, at my Black & Green Games website. Inspired by my most recent game, I’m writing about the noir genre, and how game design and fiction overlap. I plan to host interviews there, of game designers and theorist who have done fascinating work in rpg design, larp craft, transmedia and Alternate Reality Games.

If I’ve never played your games before, what’s the first one I should try?

Probably a good place to start is with Breaking the Ice. This was my first published game and is the most well known of my games. The game is about two characters who go on their first three dates.Two players try to get them to fall in love, and then see if they have what it takes to make it over the long haul. It’s a quick game that needs no prep. You can sit down and start from scratch and be done in 2-3 hours. Or take your time and play it out over several sessions.

To make characters in Breaking the Ice, you start by picking the character’s favorite color. Then the players help each other create a word web of things associated with that color, like “river” and “jazz” for the color blue, or “trees” and “organic gardening” for the color green. You pick work, hobbies and personality traits for the characters which are suggested by those words. And as you play, you roll dice to help create Attraction and Compatibilities between the two characters. First, you roll dice for making things go well. Then, if that doesn’t work, you roll dice for making things go wrong for the characters. Each player takes a turn playing their character and being the Guide, kind of like a game master, who give suggestions and awards dice to the other player.

If you want to play with more people, you can have the characters go on a double or triple date. (Or play with two teams playing a single pair of characters.)Once I ran the game for three pairs of players who took their characters on three “dates” during the opening of the first live action, fully-three dimensional dungeon crawl theme park. We used the map from the Tomb of Horrors module of Dungeons & Dragons and had a blast.

One fact that we probably don’t know about you:

I am a licensed forester in Massachusetts. The town in southern Connecticut I grew up in was an old farm town when my parents grew up there, which has become much more populated and developed. The end of town I grew up in is near the Housatonic River, and was where the last big farms were in town during my childhood. I spent long summer days with my dog running around in the woods near the river, splashing in brooks and climbing trees. Studying the forest and helping people manage their woods seemed like a great way to make a living, so I studied forestry at UMass Amherst. I took that education and went into conservation, and during the day work with landowners to help them conserve their land to help give other kids those same kinds of memories of their childhood.

What tabletop games (including digital board/card games) are you playing most right now?

I am in a campaign of Dungeon Crawl Classics. This game is part of the Old School Renaissance movement in tabletop role playing game design: hearkening back to the earliest of versions of Dungeons and Dragons™, embracing truly lethal levels of character mortality and being all about the dungeon delve. Goodman Games wrote DCC and I love the tone they hit with it: gritty and fearing for your life, but with a wickedly fantastic sense of this magical world. When you start a campaign, you start with what they call “the funnel”. Each player takes four 0-level characters into play. For a reason! If you come out of the first session with one left, you’re lucky. And the characters themselves have backgrounds that are rolled up randomly: pig farmers, mushroom farmers, tax collectors, bandits. Once they make it through the funnel, they level up, take a class and you can start breathing easy (for now!) and imagining a future for them. My current character, Iquinox, began life as an herbalist and has since become a Wizard of the Chaotic Arts. The surviving character of a fellow player happened to also be named Iquinox! So we made them brothers: one a cleric of law, one a wizard of chaos, leading to wonderful philosophical debates.

I’ve run my light fantasy story-telling/role playing game Misericord(e) at several conventions recently. It takes part of the system Meguey Baker created for her 1001 Nights game, and uses it to tell the tales of adventures that members of 13 Guilds in the town of Misericord(e) get up to. The Guilds vie for whose member can tell the best adventure tale at Midwinters, so the games you play are the guildmembers trying to get into the most interesting scrapes, so as to bring honor to their Guild. The game uses Tarot cards to set up a scenario, and to bring twists along the way.

And the other game I’m playing the most these days is Epidiah Ravachol’s Swords without Master. It is a sword & sorcery rpg, meant to let you create a story like a short story by Tanith Lee, Robert E. Howard (the creator of Conan) or Fritz Leiber, in just a few hours of play. He’s running what he calls “Sunday Morning Swords,” online on Google+ Hangouts. On Sunday mornings on the east coast play games inspired by Thundarr the Barbarian–a Saturday morning cartoon from the 80s set in a post-apocalyptic world with magic in the shattered remains of our world (which surprisingly holds up well to viewing!). I play Umsa the Zook (very similar to Ucla the Mook from Thundarr). Folks in the western part of the US started a campaign set in a world fallen into an ice age.

What are your all-time favorite tabletop games?

My top three are probably Ars Magica, Primetime Adventures, and Microscope. Ars Magica was the game that made me love role playing games. Although, we were playing in the 90s, so as was so common at that time–we used the general structure of the game and major elements of the magic system, with an original world created by my fellow players, and a homebrew, mish-mash of the GURPS rules with the AM rules set. And then mostly played freeform, based on following the lives of the characters and seeing what happened. The brilliance of the game was in giving the players permission to play different characters from varying levels of society (the Mages, their learned Companions, Soldiers and servants and Covenfolk). And the central metaphor of the magic – verbs and nouns (types of magic and forms types of actions it could take) was intuitive and supported a tremendous amount of imaginative play and authorship of a world. The simple innovation of basing play on the keep or Covenant of mages made all this possible. It’s strange that more games haven’t taken up this mantle. Many games now do have a rotating GM or more distributed world creation, so there is that.

Primetime Adventures was written in the early 2000s and was influenced by the Forge “System Matters” school of design, of which I am a part. This game was so fun and so adaptable. It uses the central metaphor of a television show to get the players on board with creating a unique premise together, and also primes you to have each person’s character have spotlight on a given session. The Fan Mail economy of the game gave input from other players and used it in plot crossroads to allow all players to weigh in on major turnings of the plot. Elegant and ground-breaking in its simplicity.

Microscope was published in 2011 and is a sideways step for rpgs. Instead of creating characters within a given setting and playing them, you take a over-arching timeline of some world’s history, and create it together. Only ocassionally do you play scenes with characters – these are scenes that answer a question a player has about a specific Event within an Era in the overall timeline. It’s a great way to create the background to a world together. And you can pick any era within the timeline and do the same thing again at that scale. In the 90s there was a game called Aria, in which you created a world to role play in by creating the history of that world – Microscope does this more simply and with greater flexibility. My favorite way to play is for 1 hour with one other person.

What draws you to make games?

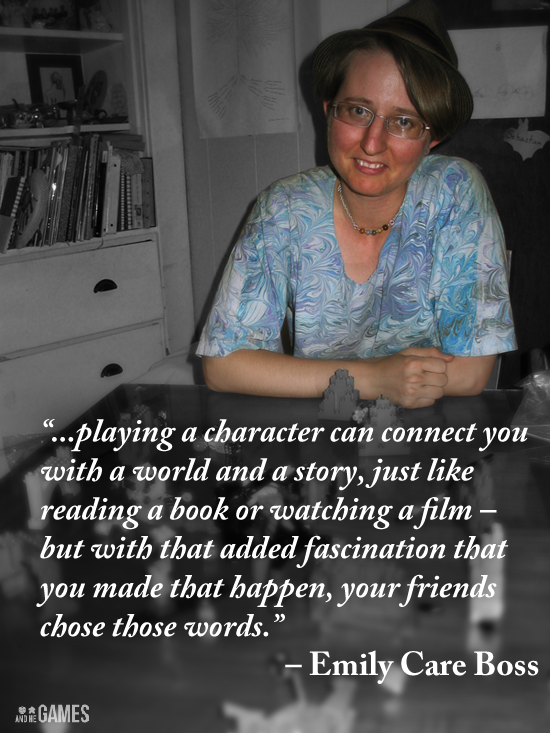

All games hold a fascination for me – creating rules that let people have fun is deeply satisfying. But role playing games in particular grab me because of the spontaneous and collaboratively creative nature of playing them. You can go as deep or as lightly immersed as you like – spend six years creating a shared world with your friends, or play for 2 hours and only be in character for fifteen minutes, tops. Each has its own rewards, and there is so much territory in between to explore.

I love how surprising the stories are in role playing games. Even when you play a game where you have scenes scripted, like the Jeepform game Doubt about action, ambition and temptation, you don’t know how the players will interpret those moments, what choices will be made.

And the emotions can go deep. Even in games that would seem to be fairly light escapist fare, playing a character can connect you with a world and a story, just like reading a book or watching a film – but with that added fascination that you made that happen, your friends chose those words. Of course, that does mean that you have to do your own editing – the many pages the author of a novel writes then throws away, or the feet of film which would once have been spilled on a cutting room floor (I suppose they languish on hard-drives nowadays), you get to live those out, and have moments or role play that are perhaps ho-hum.

But maybe that’s really what keeps me coming back to designing rpgs, to find ways to keep reducing that ho-hum to amazing ratio, in favor of the amazing. Having been to the mountaintop, I want to take other folks there, too.

What are you not naturally good at, that you’ve learned to do for your work?

Learning to GM has been one of the biggest challenges for me. I’m not a person who naturally feels comfortable in the role of entertaining a crowd. And knowing how to give the players enough that they are intrigued and want to take action, and making it so that they have choices and room to breathe, was something I had to learn. My formative role playing experiences were freeform and player-led, so creating games that had that kind of dynamic came much more naturally to me. Most of my games work sort of like board games–everyone can do any of the moves. And everyone is providing pressure for everyone else.

Watching people whom I considered to be good Game Masters do what they do, emulating them, and finally finding my own style helped get me over the hump. I’m still not terribly interested in running games that require the GM to craft a long adventure or back-story to involve the players in. I’d prefer to have a story seed, which we can all build on together.

Also, running live action freeform games gave me the best training in scene-framing and being able to craft a story through directing it. It may be similar to a director’s role in theater, and since the scenes played are most often very direct: you’re dealing with these characters emotions, their actions & reactions right there, rather than negotiating a fight between characters in a world that you use numbers to represent–it feels more natural. Guess it’s a matter of taste and experience. But both skill sets have helped me be able to write, run and play better.

Describe your process (or lack thereof) when making games. How do you reach your final product?

Ideas are fun, playtesting is hard, writing is hard, layout is fun.

The best part is definitely the initial stages of having a game idea. It’s like a puzzle or a riddle you can mull over in your mind. Whatever the kernel of the idea is, it’s fun to think about since it’s an idea that tickles me. And there are no limitations–it’s just an idea in my head, so anything is possible.

It’s super satisfying to reach a point where it is playable, but that is the point where it starts to get painful. Trying things does mean that you find out what doesn’t work. And playtesting is process that can make you feel very vulnerable. At least, I do. Boring people, or stumbling over mechanics can be tense and frustrating. I always prefer to do initial playtesting with friends who are fellow designers (if possible!) or at least friends who are inclined to understand that if it isn’t fun, that is OK. It’s all part of the process.

Once the game works, and you’re satisfied with it, that gets to my least favorite part. Writing it all out. For some reason, this part takes me the longest, and feels the least fun. Having two or three projects on the burner, or different aspects of the same project, can help–if one section gets boring, or I can’t see a way forward, then working on something else for a while relieves the pressure. Like working on the sky for a while when doing a jigsaw puzzle, then getting back to putting the trees and dancing unicorns back together again.

Layout is another fun part. As I move forward, I’m likely to work with people who do it more professionally, since crowdsourcing has made it possible to have more capital to invest in the projects, and the bar keeps getting raised. But when I can do it myself, I prefer that. It’s always fun to learn more, and the process of placing the words and images is relaxing and fun. Editing is always best left to others, of course, when you have the resources. It is just far too easy to be so burnt out by the rest of the work, or too blinded by having seen it all so many times before.

What game design-related media do you consume on a regular basis?

History, films and fiction feed my game design muse. Reading the novels and poetry of the Japanese Classical period inspired me to write my game (in progress!) City of the Moon, for the Game Chef contest in 2005. I’d love to come back to that game. More recently, poetry and tales from the Warring States period of Chinese history (5th Century BCE – 221 BCE) lead me to write King Wen’s Tower, for Fastaval last year. Film noir and noir fiction are favorites of mine, as well as the novels of Jane Austen, and the fantasy novels of Patricia McKillip. Last year I wrote Last Chance Noir, a freeform larp tool kit based on Play With Intent. And I am working on the final version of Heart of the Rose, which is very inspired by the works of McKillip and related fantasy. Maybe sometime I’ll write a game inspired by Austen.

What are some tool/programs/supplies that you wouldn’t work without?

Although I use Microsoft Word for almost all the writing I do, I often wish there was a better writing program out there. Scivener may be just that. It organizes your work into a set of documents which are nested and can easily by linked between and inter-related. I’m using it now for organzing the revision of my Romance Trilogy, and also for a historical larp about John Milton and Paradise Lost that I’m working on. It may become a go-to program for me.

Two that I’d be lost without are InDesign and Adobe Acrobat. InDesign is incredibly useful for layout and design of games and books. And I use Acrobat to created and modify pdfs constantly in my daily professional life as well as my publishing work.

What’s your playtesting philosophy? How often/early do you playtest?

For me, the most formative parts of playtesting are running the game myself for many, many groups. The feedback that one can get second hand by sending a game out to be played is very important–but there is so much information that is lost or distorted in the reporting process. Being able to observe how players react to the game, what they do with it and how it progresses, in person, is critical to design for me.

Playtesting usually starts pretty early. Trying out sections of the game helps me tune it and see what will or won’t actually work in play. And also, many times suggests ways to structure play that I hadn’t realized it needed. For example, when I was designing Under my Skin, I just ran through character creation with a fellow game designer. We made the characters, and then at the end I asked “so what core issue is your character concerned with?” And it just didn’t work. The character was complete; it had likes and needs, but it didn’t fit with this idea of an issue that they struggled with, and the ways that they fit with the other characters, too, wasn’t apparent. So, I realized that that core issue step had to come first. And everything else would spill out from it. Pick a core issue, and have others suggest areas of life that it could effect (giving everyone some buy-in in everyone else’s characters, and also giving help to each player to come up with ideas about their role). Then, when the characters are created, pick those who may be in relationships based on logical things about their background or interests–but then we could see what the dynamic would be between them: an author and a soldier being married is one thing, but an author strugglign with loneliness being married to a soldier with anger issues is a whole different thing. It’s a relationship that has energy to it, and that you can see dramatic directions immediately. Putting the game in motion–even before you get to the point of testing it out, is a critical part of the design process for me.

What are some of the biggest obstacles you’ve faced in your work, and how have you overcome them?

In writing my first three games, the Romance Trilogy, finding an audience that was receptive to those themes was a big challenge. People shied away from having real world emotions be represented in rpgs. Either from having seen it done poorly, or not wanting to deal with that kind of feeling in a recreational context. “Why pretend to go on a date when I could go on a real one?” was some of the feedback I got. My answer was, “Why do people read books about romances? Or make films?” People love these stories. Keeping with it, running the game, and having friends and colleagues who believed in them made all the difference. And not believing the criticisms–or at least having the faith to try anyway despite naysaying. And–being able to see when I was making mistakes. It’s a balance.

Another challenge is knowing when a game is done, or can be finished. Really, it’s the latter that’s the hard part for me. Knowing when a game is fun and ready to be played is not hard. But certain games end up being cul-de-sacs. Not quite a dead end, but I keep spinning around with them, not settling on the exact right answers. In some cases, it was because I hadn’t encountered the right rules set that the game premise needed as yet. When I started working on Under my Skin, I intended for it to be played as a tabletop game, and I had ideas about including “drama points” and having people “trigger” each other by acting out. There is a tabletop version now that does include those things–but the main game, which is really what the story of the game is most suited too–is played out live, as a freeform larp. But I didn’t know that kind of game existed until after I’d been working on the game for several years. And once I had played them, it took a friend to suggest it, and me some time to realize that she was right!

How do you handle life/family/work balance?

Gaming is an important part of my social life. Many of my closest friends are people I know through gaming and are people I game with regularly. As far as family, I took the novel (or is that tried and true?) approach of marrying another game designer, Epidiah Ravachol. We both get it about how nutty we are about games, so it makes it easy to understand and explain how much time we both want to spend on them. Also, we travel together to conventions for vacation. We even went to game conventions in Europe on our honeymoon!

How many hours/week do you generally devote to game design? How many to other business-related activities?

Week to week it varies a lot. I’d say on a week when I’m busy with other things I only spend 2-5 hours thinking about or working on game design. On a good week, when there is plenty of time, I’d spend about 5-15 hours a week, plus 4 or 8 hours playing games as well. In a high production time, like when I’m finishing a game, or doing a lot of playtesting, I probably spend 20-30 hours a week on them. There are many memories I have of long nights writing and doing layout leading up to going to GenCon to premier a game at a booth.

What one piece of advice would you give aspiring game designers?

Decide what you want from game design, and adjust your expectations if you find you are unhappy. For example, some people want to jump into game design and make a living doing it right away. This is much more possible than it ever has been–with crowdfunding making it possible to do more and reach more people than you could in the past. But it’s not easy to do this, and no matter what you do there will be a lot of work involved: learning, designing, refining, and meeting people. People who can give you feedback on your game, as well as help you with the parts of design you can’t do (unless you’re one of those wunderkinds who can write/draw/do amazing layout/etc!), and also support and understand where you’re coming from.

But there are many kinds of success: being a full-time paid designer, doing it part time as a for-profit enterprise, designing games to publish for the love of it and some extra cash, or simply looking at it as an artform you love and sharing your game through running it at conventions or publishing it for free online to be part of the community of play. All of these things are great. The main thing is that what you’re aiming for actually matches the time/effort/money you have to spare, and that it doesn’t drain you financially or emotionally getting there. Success can be as big a problem as failure, depending on the context!

So, pick a goal for your game design, and be prepared to adapt and change it if until you find the level of engagement that makes you feel fulfilled.

Who would you like to see answer these questions?

What’s the best advice about life that you’ve ever received?

During college, I was at a bit of a loss. I had left the first college I went to, Bryn Mawr in PA, because it was too expensive for me and my family, and I was living at home trying to figure out what to do next. Pat, a mentor of my best friend, suggested I move to the Pioneer Valley in Massachusetts. It was a liberal area, full of many colleges and other people who were thinking about the world and looking for innovative answers. I moved up there and found friends I lived communally with for many years. Went to college and found a career. I’d never felt really at home in southern Connecticut, it was pretty conservative and I was very liberal.

So the advice Pat gave me was to find my place in the world. To find communities I could feel a part of. This has made all the difference for me in life: through work, socially, romantically and in game design.